A New Common Era

- Rhiannon Evans

- Aug 5, 2019

- 4 min read

It was my mother’s birthday on the 24th of March, and so naturally I was doing that thing that I’m sure everyone does…I was looking up things that happened throughout history on the 24th of March. This led me to discover that my mother’s birth coincided with the anniversary of Queen Elizabeth I’s death in 1603, 372 years earlier exactly, or so I thought. Proudly, I informed my mother of this, and in return got more confusion than I bargained for. My father responded with “Interesting but you’ve got your calculation wrong there, look up the calendar riots of 1752.”. Now for the record 1975 (the year my mother was born) minus 1603 is 372, my A-level maths has not failed me there, but my dad did have a valid point.

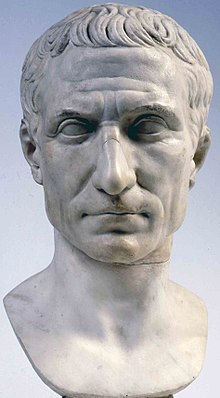

Until 1751, England used the Julian calendar, created by Julius Caesar himself. This calendar was exceptionally advanced considering how long ago it was created and did in fact include leap years, but it worked on the assumption that each year is exactly 365.25 days long, when in reality, it’s about 11 minutes less than that. This was not a problem during the Roman era as the number of years that it would take for that eleven minutes to affect astronomical observations was a lot longer than the Roman Empire lasted for. The previous calendar had 355 days in most years and something called an intercalary month every second or third year, this intercalary month was formed by inserting 22 or 23 days after the first 23 days of February. The occurrence of these years wasn’t systematic, but rather decided by the pontifices (or high priests). This was an issue because these pontifices were also politicians, meaning that they could lengthen years that they or their political allies were in office. Intercalations were often determined quite late, and therefore the average Roman citizen often did not know the date, particularly if they were some distance from the city. For these reasons, the last years of the pre-Julian calendar were later known as "years of confusion". So, Caesar had a big job ahead of him when he decided to fix these dating issues that the Roman Empire was having, and thus I feel that we can forgive him for his little 11-minute oversight.

As time went on, these 11 minutes became more and more prominent as the movement of the sun was not fitting with our understanding of the 24-hour day. Understandably, Pope Gregory XIII decided that something needed to be done, especially as it was becoming increasingly impossible to pin down the dates of Easter (which is always the first Sunday after the first full moon occurring after March 21st – the March equinox). However, moving the entirety of Europe onto a new system of time is easier said than done. In 1582, France, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Spain all made the switch to the new Gregorian calendar by order of the Pope, but he had far less control over Britain, which had split from Rome under Henry VIII and therefore had no obligation to follow this new, seemingly more pious calendar. By the 1700s, newspapers had become more popular, and working on a different calendar system was no longer working for Britain. So, in 1750 the Calendar (New Style) Act introduced the Gregorian Calendar to the entirety of the British Empire (beforehand many different locations within the empire were using different calendars, which proved to be a hinderance to further conquering). This meant that 1751 was a shorter year, lasting just 282 days from 25th March (the first day of the Julian calendar) to 31st December, before beginning the next day on the 1st January 1752. Now New Year’s Day matched between the two regions, but the years were still different lengths. To correct this, it was decided that 2nd September 1752 would be followed by 14th September 1752, and the 11 days between them came to be known as “the lost days”.

Now this next part is debated, as historians are unsure as to whether or not the common people of the era were aware of how this calendar change affected their lives, but the story is that this caused riots in the streets, with people exclaiming “Give us our eleven days”. This may have simply been a misinterpretation of a William Hogarth painting from 1975, but it is still true that some people truly believed that because these 11 days were skipped, their lives would now be 11 days shorter overall (preposterous as calendars are just human constructs and how no bearing over lives or orbits of planets at all). This was even more of an injustice as it was seen to be a movement back towards a religion that the country had so violently broken away from. A rebranding was necessary, thus why BCE (Before the Common Era) is far more common than BC (Before Christ) which is seen as less religious.

On a lighter note, some decided to use this opportunity to make some money. A man called William Willett supposedly bet that he could dance non-stop for 12 days and 12 nights, and therefore, beginning on the evening of September 2nd 1752, William Willett danced all through the night. The next morning, he claimed his bets as it was now September 14th 1972, 12 days later and yet no time had passed!

With regard to my original confusion, I now know that we use the modern calendar to describe the dates on which events occurred in the Tudor era, so Elizabeth I did died on the 24th of March 1603, but to her contemporaries, this would've actually been March 24th 1602.

Comments